I’m in Omaha, Nebraska, selling grams and half grams of coke to indie rock kids and wannabe indie rock kids. Everyone is earnest and hardworking and very welcoming. They live in big, drafty houses with slanted windows and sloping wood floors. I stand out on the front stoop with my shoulders hunched and tree lined streets twisting all around me, a cardboard cup of sugary black coffee steaming between my hands. This is real America—closed off, hunkered down and full of food. You can almost smell the fat of the land. The indie rock kids have artfully disheveled hair and blue eyes. They think I’m one of them and are surprised to find out I’m from New York. “What are you doing here?” they ask, as they let me through the front door and lead me directly into the basement. In Omaha, all the action takes place in basements.

“Right now I’m selling drugs,” I tell them. Presently, I’ve got 24 tennis balls filled with coke in my canvas Army duffel bag. My guy in New Mexico (whom I met through my guy in Minneapolis, whom I met through a friend of a friend of Will’s) showed me how to pop open the balls along the seam and slide the baggies inside. Once filled, the balls still bounce and everything, although you probably wouldn’t want to risk smacking them around with a racket. My guy told me how kids toss the balls out of car windows to runners waiting on corners, eliminating the need for a suspicious exchange. How ingenious, I thought, turning the stuffed ball over and over in my hands, until the shape of the concrete gray seam burned itself into my eyes.

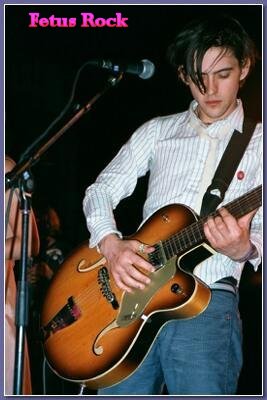

I sat on an under stuffed, stained couch listening to a skinny, pockmark-faced prodigy emoting his guts out over the jangle of secondhand guitars. No matter where I am or what year it is, the rock n’ roll story is always the same. The band try hard to be naturals while the significant others (in this case, all girls) drink PBR out of cans and cautiously snort tiny lines of the stuff I provided. Some of them are only 15—ill formed bundles of tits and hair and geo-political concerns. They stare at me and when I catch them looking they quickly blurt out that they like my bangs. I feel like telling them it’s OK, I don’t know what sexuality I am, either. Meanwhile, the guys invite me to shows, shows and more shows. Having a dealer around provides a much needed sense of validity. Now that

the first wave of Omaha bands have made it big, there’s a whole set of kids eager to follow suit. They’re obsessed by Connor Oberst and

Saddle-Creek Records and the scene that they created, but if you ask them about it they’ll flatly deny it. “Oh, yeah, I used to listen to them, before they sold out.” Over a communal meal of Boca burgers, rice and pinto beans, they solemnly inform me that they’ll never appear on MTV. Someone produces a copy of the

NY Times magazine from last week, in which Conner Oberst is prominently featured. Everyone scoffs. “Getting into some corporate mag is not what this music thing is all about,” the lead singer states, “You know what I’m saying?” He stares at me, his eyes full of passion. I stare back at the line of whiteheads on his forehead and don’t say a word, my mind completely blank.

By evening the place is packed and I unload a few more balls. I don’t feel like a party so I borrow someone’s parka and go out to the garage with Kafka’s The Blue Octavo Notebooks tucked into my jeans. Lately, it’s all I can read. Out on the driveway I see some girls playing Double-Dutch in the setting sun. I wave at the mother across the street and motion to her that I’ve got the girls covered. She waves back and goes into the house. It’s amazing how trustworthy people are out here. I could be anyone. I light a spliff and watch the treetops burn orange. The telephone wires and TV antennas are in silhouette. I relax into the rhythm of the ropes slapping the ground. Behind me, in the house,

New Order is playing:

“I lived my life in a valley, I lived my life on a hill

I lived my life on alcohol, I lived my life on pills…”

Suddenly one of the girls shouts and points up to the sky. The jumper stops jumping and the rope turners drop the ropes. They slink around on the driveway like live snakes before becoming still.

“What is it, what’s the matter?” I run over and look up.

“What? What?” I demand.

“There! There!”

Then I see it. Something burns brightly in the sky above our heads. An aluminum colored curl hangs out of the dark blue twilight, as silent and gray as a ghost. My mind immediately races through the possibilities: a trick of the light…a plane…a meteor or some other astronomical event. None of these seem to fit the apparition that we’re seeing. It’s happening! I scream out inside my head, but I don’t know what. There’s something oddly familiar about the shape. I feel a fear in my chest—the fear of being watched, but as the lone adult in the front yard, I quickly suppress it. The curl vanishes in the next instant, as though brushed away by an invisible hand. A few seconds pass before the girls turn to me, pigtails and puffy jackets, eyes wide and blinking.

“What was that?” they want to know. “In the sky. What was it?”

“That? Oh, that was nothing, just a satellite,” I say, quickly scanning the street to see if their was another adult in view. There were no moving shapes among the mailboxes, trashcans and parked cars—no one to run over to and scream, “Did you see that? What the fuck!”

“Yeah, we put satellites way up there in the sky, so they can take pictures and send pictures back. For TV.”

“We have a satellite dish,” a buck-toothed red head announced.

“See? There you go. No big deal.”

“We have 171 channels.”

“Really? That’s great. But I bet sometimes you still can’t find anything to watch?”

I joked around with the kids for a little longer—laughing with them made me feel better too. But I wanted to get inside. It was dark and cold and the street didn’t seem so friendly anymore. I went across the street and told the mother I had to be going, keeping my eyes low while she thanked me so that she wouldn’t see that I was lit. As I headed back across the street I heard the girls chirping about how they saw a satellite in the sky. “That’s nice,” the mother responded, before the door clicked shut. I breathed a sigh of relief. If everything was still OK in her world, than it was still OK in mine.

It wasn’t until an hour or so later, when I was counting my tennis balls and packing them in the middle of my duffel bag, that I realized the shape and color of the seam that had fascinated me so much was identical to that of the mysterious phenomenon I’d seen in the sky.